If you’ve been following me for a while, you probably have heard something about the Common Lexicon for Education. Or you may have read about it through a metaphor of music.

If you are curious about the ideas underlying the development of this Common Lexicon, you’ve come to the right place, because we have put them on paper as the Common Lexicon LIFE* Cycle!

But before we dive into that, a bit more context:

What is the purpose of a Common Lexicon?

In essence, a Common Lexicon strives for a common meaning of concepts, among people working in a domain with many different contexts, stakeholders and perspectives.

What do you need common meaning for?

Common meaning among people improves collaboration without losing autonomy (remember: The University is an Orchestra) and it is an absolute necessity if we want to create and maintain flexible, transparent software and technical interoperability, especially in domains that have to deal with different contexts, stakeholders and perspectives (such as, you guessed it: Education!).

But don’t we have dictionaries / information models / reference architectures / ontologies / knowledge graphs / […] for that?

In part, yes. The steps we have taken so far are obviously strongly based in these fields of expertise. However, interestingly, while these types of models are very good in representing the semantics of specific terms (dictionaries) or the whole (information models/reference architectures/ontologies/knowledge graphs), they are generally not very successful in being a tool to come to a common understanding among people that come from different specific perspectives within the whole. This is my experience in my job as an Information Manager Education, anyway.

Thus, I believe there lies great opportunity to build on these ideas from the perspective of collaboration, communication, learning and alignment in organizations.

Where did you get these ideas?

Mostly, from my dissertation on business IT-alignment in complex organizations (i.e., many different stakeholders and quickly changing conditions). In this work already, I referred to business-IT alignment in relation to common meaning, using the following definition:

“A common interpretation and implementation of what it means to apply IT in an appropriate and timely way.”

Also, a key take-away from my PhD research, is that alignment in complex organizations (and by implication, common meaning) is dynamic and ever-changing, and can only really emerge through collaboration and interaction between people from different contexts and backgrounds. This implies that these people not only need to continuously work with, but also on common meaning. In other words: for these types of organizations to successfully address the complexity they’re facing, we somehow need to democratize semantic modelling itself.

How can a Common Lexicon help?

A Common Lexicon, and in particular the instance Common Lexicon for Education, should be a tool to facilitate these dynamic co-evolutionary processes to continuously and collaboratively work on common meaning and with that, on alignment.

How does this relate to the Common Lexicon LIFE* Cycle?

As said, the development and application of the Common Lexicon for Education is clearly embedded in my scientific background in business-IT alignment in complex conditions. However, the defining principles and scientific foundations of the Common Lexicon for Education have so far have remained untouched or implicit. And I would really like to change that!

Therefore, we (me and my dear and linguistically very talented colleague Vera Kamphuis) developed the Common Lexicon LIFE Cycle:

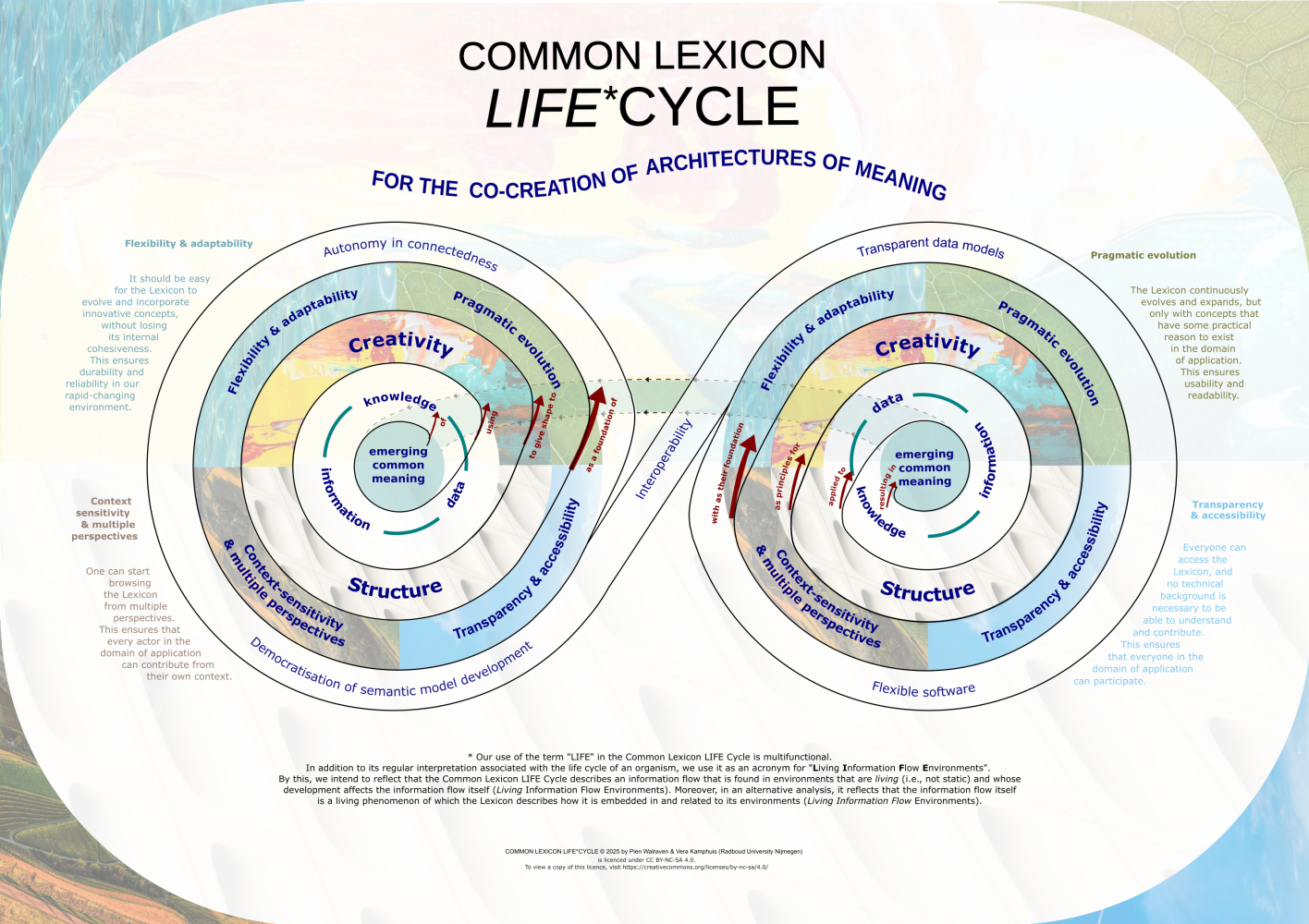

- As a visualization of the vision behind the Common Lexicon for Education, focusing on how common meaning emerges in the first place and

- As a starting point for the development of its scientific foundations, to begin with, in collaboration with Radboud University and DEMAND.

Apart from its core (emerging common meaning), its ingredients (data – information – knowledge) and its tools (creativity & structure), a very important part of the Common Lexicon LIFE Cycle consists of its design principles for Common Lexicons:

- Flexibility & adaptability

- Pragmatic evolution

- Transparency & accessibility and

- Context-sensitivity & multiple perspectives

These design principles live and breathe the founding ideas of my PhD research, and build upon them.

In the outer ring of the Common Lexicon LIFE Cycle Lemniscate, you see the things that I believe become possible, with the abovementioned design principles as their foundation; using creativity and structure; applied to data, information and knowledge, and resulting in emerging common meaning.

Furthermore, this common meaning tends to change – through the dynamicity of the environment and the multitude of perspectives. And thus the same process needs to be undertaken again and again, to ensure meaningful organizations and IT systems, based on meaning defined by people.

What’s next?

I am very happy to announce that the first master’s students in Information Sciences at Radboud University have just started doing their thesis research on different aspects of the Common Lexicon for Education.

Furthermore, our working group at Radboud University is working hard to further develop the Common Lexicon for Education and its underlying ideas. In parallel, we strive to make a positive impact on educational practice by collaborating with as many perspectives as possible at Radboud University itself, but also at the levels of SURF, Npuls, Edustandaard and the European Digital Education Hub.

Of course, we are interested in any new and enriching perspectives and are very open to possible collaborations. So do you want to collaborate or know more? Join our SIG (https://www.linkedin.com/groups/13190740/) and/or contact me!